Mission San Diego de Alcalá Founded (1769)

Facts

1st Mission in Alta California

Named for St. Diego of Alcala

Original Indians, linguistically related to the Yuman Indians of AZ

1774 – drought forced the fathers to move the mission inland

A year later, Indians attacked & burnt it down

Casa del Padre Serra (built in 1774) – his bedroom is the only one to survive

American military occupation from 1846 until President Lincoln returned it to Catholic Church in 1862

Striking windows, built up high for defense and so they would not give under the weight of the adobe

The first of the twenty-one California missions, Mission San Diego de Alcalá is named after the 15th-century saint, Didacus of Alcalá, more commonly known as Saint Diego. Founded by Father Junipero Serra on July 16, 1769, it is here where the Spanish religious and political dream to begin an Alta California mission chain first became reality.

Originally located on a hill overlooking the bay, a drought in 1774 forced the mission fathers to move Mission San Diego about six miles inland to its present location, closer to the San Diego River, to gain access to more favorable agricultural lands and the local Indian villages.

The native Tipai-Ipai Indians were resistant to colonization and within weeks after the mission’s founding violence had resulted in deaths for both the Indians and missionaries. In 1775, discontented with rules and regulations, hundreds of local Tipai Indians attacked the mission, causing great damage to the building and killing Father Jayme, who would become California’s first Christian Martyr. Fearing another raid, the padres rebuilt the mission according to the specifications of an army fort.

As the mission population grew, so too did the need for a larger church. The Franciscans employed master mason Miguel Blanco to construct the building, resulting in a design considered old fashion even at the time of its completion. The church features striking windows, built high for protection from intrudres, and also to prevent them from collapsing under the weight of the adobe walls. When the roof cracked in 1811, large buttresses were added to the front of the mission. This addition came just in time – the extra support allowed the mission to survive the 1812 earthquake.

One of the most striking features of this mission is the 46-foot tall campanario, or bell wall, which holds five bells. The largest of these bronze bells is named Mater Dolorosa, and weighs a staggering 1,200 pounds. Common to all the missions, bells served an array of purposes: they announced the time for mass, work, meals, and siestas. Of course, they also warned of danger, tolled to honor the dead, rang to celebrate peace, and proclaimed the arrival of guests.

Father Junipero Serra’s legacy remains at this southern most of the California missions. Built in 1774, La Casa de Padre Serra, is where the mission idealist once slept. It is believed that this room is the only original room to have survived Indian attacks and natural disasters.

Mission San Diego’s military past has been eventful. The American military occupation of the mission began in 1846 and lasted 16 years, until President Abraham Lincoln signed a proclamation returning the mission to the Catholic Church in 1862.

Today, the church and a newer chapel, La Capilla de San Bernardino, combine to serve as religious center for Mission San Diego’s still large and active parish.

From Inside the California Missions

© David A. Bolton

Mission San Diego de Alcalá video tour presented by California Missions Foundation. Video courtesy Cultural Global Media archives and music provided by our esteemed CMF member Dr. Craig Russell and vocal ensemble Chanticleer.

California Missions Foundation

https://californiamissionsfoundation.org/

The First Atomic Bomb Tested (1945)

Trinity Test -1945

The efforts of the Manhattan Project finally came to fruition in 1945. After three years of research and experimentation, the world’s first nuclear device, the “Gadget,” was successfully detonated in the New Mexico desert. This inaugural test ushered in the nuclear era. Read below for more information about the test, its aftermath, and impacts.

Location

The test was conducted at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range, 230 miles south of Los Alamos. The site, located in the Jornada Del Muerto Desert, was chosen for its isolation, flat ground, and lack of windy conditions. Manhattan Project leaders also considered sites elsewhere in New Mexico, as well as in Texas and California.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory during the Manhattan Project, called the site “Trinity.” The Trinity name stuck and became the site’s official code name. It was a reference to a poem by John Donne, a writer cherished by Oppenheimer as well as his former lover Jean Tatlock.

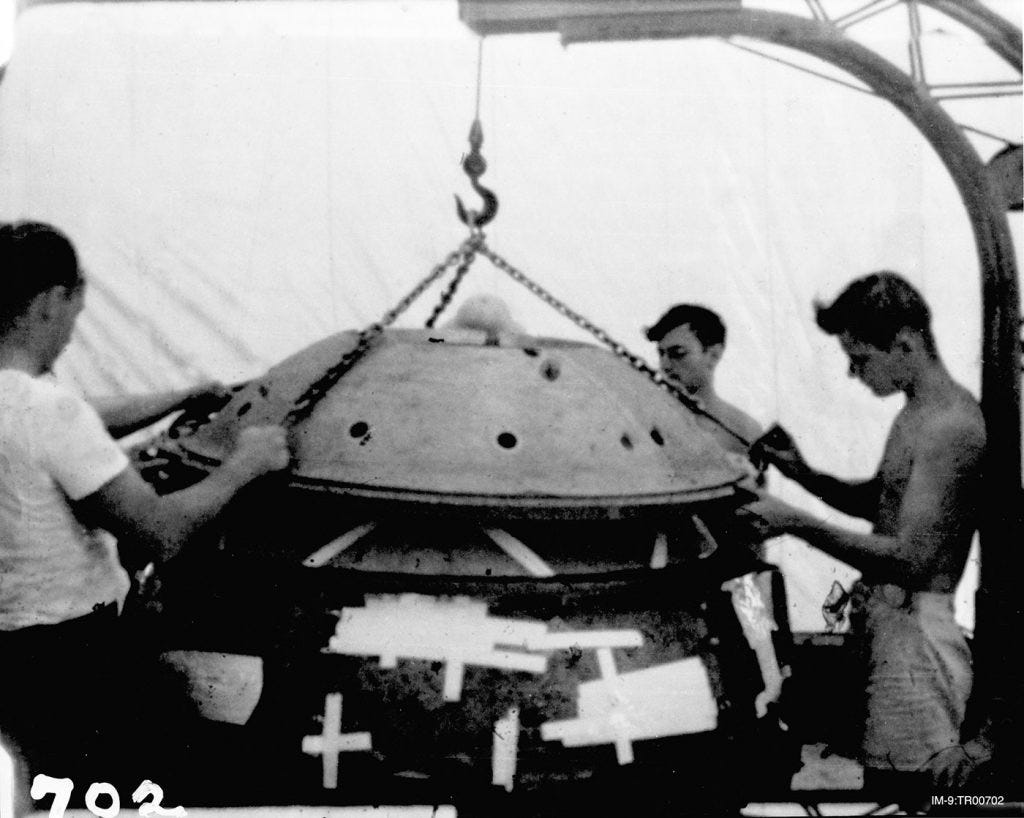

The Gadget

The nuclear device detonated at Trinity, nicknamed “Gadget,” was shaped like a large steel globe. Like the Fat Man bomb dropped on Nagasaki, it was a plutonium implosion device. Plutonium implosion devices are more efficient and powerful than gun-type uranium bombs like the Little Boy bomb detonated over Hiroshima.

Plutonium implosion devices use conventional explosives around a central plutonium mass to quickly squeeze and consolidate the plutonium, increasing the pressure and density of the substance. An increased density allows the plutonium to reach its critical mass, firing neutrons and allowing the fission chain reaction to proceed. To detonate the device, the explosives were ignited, releasing a shock wave that compressed the inner plutonium and led to its explosion.

Jumbo

One unique device that appeared at the Trinity site in the days leading up to the test was Jumbo. Jumbo was a massive cylindrical steel container. Its production was ordered, at a cost of $12 million, by General Leslie Groves as a containment vessel, because of concerns that the test would not be a success. The plan was for the plutonium core to be imploded inside Jumbo. In the event that the Gadget “fizzled,” or did not properly detonate, Jumbo would preserve the bomb’s rare plutonium for future experimentation.

By the time final preparations for the test were underway, however, scientists were confident that the test would work and so Jumbo was not used. Instead, it was suspended from a steel tower 800 meters from ground zero during the test. The tower was destroyed, but Jumbo remained intact. After the war, the Army blew the ends off Jumbo in an unsuccessful attempt to destroy it, and today its remains can be seen at the Trinity Site.

Preparation for the Test

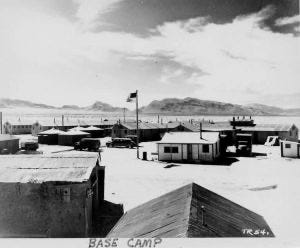

There was a considerable amount of construction that needed to be done in order to prepare the barren desert for its role as a nuclear test site. Kenneth Bainbridge was assigned to lead the test site’s development. In addition to the myriad technical materials required for the Gadget’s successful detonation, a base camp was constructed with ample security measures, albeit Spartan living conditions. Additionally, miles of roads were paved to transport materials to the test site, and multitudes of electrical wires and cables were constructed in order to provide the power that would detonate the gadget during the eventual test.

Much of the preparation for the Trinity test encountered setbacks. The challenges faced in developing the Trinity site were numerous and multifaceted, and there were often close calls that could have jeopardized the outcome of the entire project. Some were almost comical, such as when Kenneth Greisen was pulled over for speeding in Albuquerque while he was driving detonators to Trinity four days before the test. He could have been delayed by several days had the officer checked the contents of his trunk.

A more ominous event was the actual process of winching the Gadget to the top of its tower at the test site. As it was being raised to the top, it came partially unhinged and began to sway. Many observers were stricken with panic at the possibility of the bomb accidentally falling from the tower and detonating, but the Gadget was eventually righted and made its way to the top of the tower without further incident.

Yet Manhattan Project officials were probably most concerned about several failed preliminary tests as they prepared for the actual test. On July 14, just two days before the scheduled date for the Trinity test, Edward Creutz led a dress rehearsal practice test without any nuclear materials. Despite the success of a 100-ton TNT blast in May, Creutz’s test was unsuccessful, and the device failed to detonate.

Fortunately for the scientists concerned by this result, Hans Bethe was able to demonstrate the next day that the test failed because of overworked practice equipment. Since the equipment for the Trinity test was comparatively unused, many scientists were comforted by Bethe’s findings.

Scientists were also frustrated by a test run on the fourteenth by Don Hornig. After spending several months working on the X-5 firing unit that would trigger the bomb’s detonation, Hornig had conducted several tests of his device with no problems. However, his final test failed, provoking many of the same fears as Creutz’s failed experiment. The same issue plagued both tests: the practice materials simply had become worn down after several months of experimentation.

Nevertheless, several scientists participated in an informal pool, betting on how many or how few kilotons of TNT would actually be yielded by the bomb’s explosion. Pessimism swirled around the test site. Unfortunately for the scientists at Trinity, it wasn’t the only thing in the air. A dedicated meteorology team, led by Jack Hubbard, had been stationed at the Trinity site since the end of June. They tracked weather patterns and made critical analyses in order to predict what the weather would be doing on July 16. Their reports called for a storm.

As predicted, wind and rain began to batter the Trinity tower on the night of July 15. Many were worried that the test would be forced to be postponed for several days. Any delay would have been a major psychological strain on a project that had become tremendously stressful for its participants as the project entered its final leg.

This short video provides color footage of the explosion of the Gadget plutonium bomb at the Trinity site. Thanks to Trinity Remembered for providing the Atomic Heritage Foundation with this video.

http://www.trinityremembered.com/

https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/history/trinity-test-1945/

The End of a Dynasty (1999)

On this day, John F. Kennedy Jr., his wife Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, and her sister Lauren Bessette tragically died in a plane crash off the coast of Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts. Their untimely deaths marked the end of a prominent American political dynasty.

On July 16, 1999, John F. Kennedy, Jr.; his wife, Carolyn Bessette Kennedy; and her sister, Lauren Bessette, die when the single-engine plane that Kennedy was piloting crashes into the Atlantic Ocean near Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Jr., was born on November 25, 1960, just a few weeks after his father and namesake was elected the 35th president of the United States. On his third birthday, “John-John” attended the funeral of his assassinated father and was photographed saluting his father’s coffin in a famous and searing image. Along with his sister, Caroline, he was raised in Manhattan by his mother, Jacqueline. After graduating from Brown University and a very brief acting stint, he attended New York University Law School. He passed the bar on his third try and worked in New York as an assistant district attorney, winning all six of his cases. In 1995, he founded the political magazine George, which grew to have a circulation of more than 400,000.

Always in the media spotlight, he was celebrated for the good looks that he inherited from his parents. In 1988, he was named the “Sexiest Man Alive” by People magazine. He was linked romantically with several celebrities, including the actress Daryl Hannah, whom he dated for five years. In September 1996, he married girlfriend Carolyn Bessette, a fashion publicist. The two shared an apartment in New York City, where Kennedy was often seen inline skating in public. Known for his adventurous nature, he nonetheless took pains to separate himself from the more self-destructive behavior of some of the other men in the Kennedy clan.

On July 16, 1999, however, with about 300 hours of flying experience, Kennedy took off from Essex County airport in New Jersey and flew his single-engine plane into a hazy, moonless night. He had turned down an offer by one of his flight instructors to accompany him, saying he “wanted to do it alone.” To reach his destination of Martha’s Vineyard, he would have to fly 200 miles—the final phase over a dark, hazy ocean—and inexperienced pilots can lose sight of the horizon under such conditions. Unable to see shore lights or other landmarks, Kennedy would have to depend on his instruments, but he had not qualified for a license to fly with instruments only. In addition, he was recovering from a broken ankle, which might have affected his ability to pilot his plane.

At Martha’s Vineyard, Kennedy was to drop off his sister-in-law Lauren Bessette, one of his two passengers. From there, Kennedy and his wife, Carolyn, were to fly on to the Kennedy compound on Cape Cod’s Hyannis Port for the marriage of Rory Kennedy, the youngest child of the late Robert F. Kennedy. The Piper Saratoga aircraft never made it to Martha’s Vineyard. Radar data examined later showed the plane plummeting from 2,200 feet to 1,100 feet in a span of 14 seconds, a rate far beyond the aircraft’s safe maximum. It then disappeared from the radar screen.

Kennedy’s plane was reported missing by friends and family members, and an intensive rescue operation was launched by the Coast Guard, the navy, the air force, and civilians. After two days of searching, the thousands of people involved gave up hope of finding survivors and turned their efforts to recovering the wreckage of the aircraft and the bodies. Americans mourned the loss of the “crown prince” of one of the country’s most admired families, a sadness that was especially poignant given the relentless string of tragedies that have haunted the Kennedy family over the years.

On July 21, navy divers recovered the bodies of JFK Jr., his wife, and sister-in-law from the wreckage of the plane, which was lying under 116 feet of water about eight miles off the Vineyard’s shores. The next day, the cremated remains of the three were buried at sea during a ceremony on the USS Briscoe, a navy destroyer. A private mass for JFK Jr. and Carolyn was held on July 23 at the Church of St. Thomas More in Manhattan, where the late Jackie Kennedy Onassis worshipped. President Bill Clinton and his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, were among the 300 invited guests. The Kennedy family’s surviving patriarch, Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, delivered a moving eulogy: “From the first day of his life, John seemed to belong not only to our family, but to the American family. He had a legacy, and he learned to treasure it. He was part of a legend, and he learned to live with it.”

Investigators studying the wreckage of the Piper Saratoga found no problems with its mechanical or navigational systems. In their final report released in 2000, the National Transportation Safety Board concluded that the crash was caused by an inexperienced pilot who became disoriented in the dark and lost control.

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/jfk-jr-killed-in-plane-crash

Existence of Watergate tapes is revealed in live testimony (1973)

On July 16 ,1973—a little more than a year after the break-in at the Watergate Hotel led to a widening scandal—explosive news is revealed during a live broadcast of the Watergate hearings in the Senate: A secret taping system inside the White House had recorded all of President Richard Nixon’s telephone calls and in-person conversations.

Alexander Butterfield, deputy assistant to the president during Nixon’s first term, had informed Senate investigators about the existence of these White House recordings a few days earlier and explained how the secret system worked. Butterfield then shared the shocking revelation during live testimony before a Senate committee.

Butterfield, who said he felt conflicted about the reveal, later faced serious consequences. He lost his job as head of the Federal Aviation Administration, where he worked after Nixon’s re-election, and couldn’t find work for two years. He lost many friends who considered him a traitor for outing the president.

“I hated to be the guy who had to tell about the tapes,” Butterfield said in a conversation for StoryCorps on April 27, 2016. . “But I saw these guys I really liked and admired going off to jail. And I realized Nixon exploited their loyalty.”

In the following weeks, Nixon reportedly ordered the White House staff to disconnect the White House taping system, and he refused to turn over the tapes to Senate investigators. The president filed appeals to several subpoenas ordering him to turn over the tapes. He proposed to special prosecutor Archibald Cox that U.S. Sen. John Stennis summarize the tapes for investigators, but Cox refused. On October 20, 1973, Nixon ordered the firing of Cox in an infamous episode known as the Saturday Night Massacre.

It wasn’t until April 29, 1974 that Nixon said that he would release transcripts of 46 taped conversations in response to the subpoena the previous year. The presidency continued to unravel as the investigation continued, and Nixon announced his resignation on August 8, 1974.

Although the recordings implicated Nixon and members of his administration in the Watergate cover-up, it was the president who decided to install the taping system in the Oval Office in 1971. Nixon put Butterfield in charge of the project, carried out with Secret Service agents. The president said he wanted the tapes available as a way to correct the record if necessary, and to document policy decisions discussed in the office.

Nixon said he wanted the tapes to be a well-kept secret. Later, in his memoir RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, the former president wrote that he thought the existence of the tapes would never be revealed.

The National Archives digitized and re-released the Nixon White House Tapes, available online through the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum. The last tapes, which recorded more than 3,000 hours, were released in 2013.

Butterfield is the subject of the 2015 book The Last of the President’s Men by Bob Woodward, one of the two Washington Post journalists whose investigative reporting broke the news of the Watergate cover-up.

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/watergate-tapes-revealed-in-live-testimony

Apollo 11 Departs Earth (1969)

At 9:32 a.m. EDT, Apollo 11, the first U.S. lunar landing mission, is launched on a historic journey to the surface of the moon. After traveling 240,000 miles in 76 hours, Apollo 11 entered into a lunar orbit on July 19.

The next day, at 1:46 p.m., the lunar module Eagle, manned by astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, separated from the command module, where a third astronaut, Michael Collins, remained. Two hours later, the Eagle began its descent to the lunar surface, and at 4:18 p.m. the craft touched down on the southwestern edge of the Sea of Tranquility. Armstrong immediately radioed to Mission Control in Houston a famous message, “The Eagle has landed.” At 10:39 p.m., five hours ahead of the original schedule, Armstrong opened the hatch of the lunar module. Seventeen minutes later, at 10:56 p.m., Armstrong spoke the following words to millions listening at home: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” A moment later, he stepped off the lunar module’s ladder, becoming the first human to walk on the surface of the moon.

Aldrin joined him on the moon’s surface at 11:11 p.m., and together they took photographs of the terrain, planted a U.S. flag, ran a few simple scientific tests, and spoke with President Richard M. Nixon via Houston. By 1:11 a.m. on July 21, both astronauts were back in the lunar module, and the hatch was closed. The two men slept that night on the surface of the moon, and at 1:54 p.m. the Eagle began its ascent back to the command module. Among the items left on the surface of the moon was a plaque that read: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot on the moon–July 1969 A.D.–We came in peace for all mankind.” At 5:35 p.m., Armstrong and Aldrin successfully docked and rejoined Collins, and at 12:56 a.m. on July 22 Apollo 11 began its journey home, safely splashing down in the Pacific Ocean at 12:51 p.m. on July 24.

There would be five more successful lunar landing missions, and one unplanned lunar swing-by, Apollo 13. The last men to walk on the moon, astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt of the Apollo 17 mission, left the lunar surface on December 14, 1972. The Apollo program was a costly and labor intensive endeavor, involving an estimated 400,000 engineers, technicians, and scientists, and costing $24 billion (close to $100 billion in today’s dollars). The expense was justified by President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 mandate to beat the Soviets to the moon, and after the feat was accomplished, ongoing missions lost their viability.

World’s first parking meter installed (1935)

The world’s first parking meter, known as Park-O-Meter No. 1, is installed on the southeast corner of what was then First Street and Robinson Avenue in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma on July 16, 1935.

The parking meter was the brainchild of a man named Carl C. Magee, who moved to Oklahoma City from New Mexico in 1927. Magee had a colorful past: As a reporter for an Albuquerque newspaper, he had played a pivotal role in uncovering the so-called Teapot Dome Scandal (named for the Teapot Dome oil field in Wyoming), in which Albert B. Fall, then-secretary of the interior, was convicted of renting government lands to oil companies in return for personal loans and gifts. He also wrote a series of articles exposing corruption in the New Mexico court system, and was tried and acquitted of manslaughter after he shot at one of the judges targeted in the series during an altercation at a Las Vegas hotel.

By the time Magee came to Oklahoma City to start a newspaper, the Oklahoma News, his new hometown shared a common problem with many of America’s urban areas—a lack of sufficient parking space for the rapidly increasingly number of automobiles crowding into the downtown business district each day. Asked to find a solution to the problem, Magee came up with the Park-o-Meter. The first working model went on public display in early May 1935, inspiring immediate debate over the pros and cons of coin-regulated parking. Indignant opponents of the meters considered paying for parking un-American, as it forced drivers to pay what amounted to a tax on their cars, depriving them of their money without due process of law.

Despite such opposition, the first meters were installed by the Dual Parking Meter Company beginning in July 1935; they cost a nickel an hour, and were placed at 20-foot intervals along the curb that corresponded to spaces painted on the pavement. Magee’s invention caught on quickly: Retailers loved the meters, as they encouraged a quick turnover of cars–and potential customers–and drivers were forced to accept them as a practical necessity for regulating parking. By the early 1940s, there were more than 140,000 parking meters operating in the United States.

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/worlds-first-parking-meter-installed

https://www.history.com/

Thanks, Daniel. The video is a good reminder of Serra International’s work to promote vocations to the priesthood. It’s an other-worldly feel.